#East Bank Baker Lake Trail

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Queerfully Cheerful Baker Lake

This is a subjective experience and does not necessarily endorse or promote anything in particular. This first and foremost is a memoir. For clarity, I’ve lived in the Pacific Northwest my entire life; and, I do firmly believe in Mt Baker National Park you have a smorgasbord of beauty to choose from. From lakes to towering peaks, and anything in between, you are likely to find a slice of experience that speaks to you. I’ve traveled, adventured, gotten into & out of trouble, and continued on with living my life like a well-to-do trooper. Baker lake was and continues to be, my break or pause from the everyday doldrums of city life. (Eventually, I intend on bringing my life partner to the area, so she can see it for herself). The first time I came here (as far as my memory serves me), was in high school. My cross country team was taken there by our coaches in July. I believe it was mid-July actually. The drive seemed extraordinarily long (even though a two or three-hour trip really isn’t that excessive). I was just a jittery ferret child. I had to be moving on the constant or my legs would hum in agony. I later learned this is called “restless leg syndrome?” As my “happy feet,” continued to tap and noisily intrude upon my team-mate’s slumber, I noticed we were finally at our destination. She seemed pissed off but no matter. We were here. There was a spot for tents, RVs, tables, pet runs, and of course, the lake itself. Across the lake, about 200 or 300 meters away I would say, there was a rope swing attached to a thick-ass Douglas Fir branch. One of our shot putters told me after we got back; said, that they swung repeatedly from the branch in question, on a separate trip. Regardless, I intend to write more about sillier matters. Essentially, our set-up time was cut in half because parents volunteered to help. Meanwhile, like a true blue spazz, I neglected to help; decided, to storm off like a banshee, rip off my shirt and longer sweat pants, and jump in the lake. Mind you, I wasn’t a complete degenerate: I had a bra and running shorts on. I wasn’t spatially aware either, so I soaked my coach with water from the leap as well. He laughed a bit but I do not necessarily recall what told me. Anyway, cross country for those who do not know, is a form of masochistic enjoyment. So, if he was angry enough to yell, “alright, you need to give 11 miles right the fuck now,” I wouldn’t have flinched or winced. Those were the days I could run consistently for hours at a time. The days my body conformed to peak performance standards. With that said… If memory once again serves me correct then I do believe we were located near the east bank trail. The trail goes on for about 9 miles. I BELIEVE we ran the entire length. According to those cool topographic maps, the elevation gain == 500 feet. The peak height matches about 1,000 feet. There weren’t a lot of roots, so if you have strong legs, but weak ankles you’d probably be okay. Of course, I’m not an authority on weak ankles. One of the girls I ran with at the time DID make me feel weak at the ankles, but I didn’t have a clue why that would have been a “thing.” (I’m an admitted late bloomer in the realm of bisexuality and sexual awakening). Personally, I preferred hanging tight towards the middle of the pack rather than follow her the whole time. The stringy moss, old-growth trees, made me feel like I was in a scene from Lord of the Rings. “Are we taking the Hobbits to Isengard?” Certainly, there’s to expound upon but I’ll save those sentences for a second posting. Welcome to the blog, even if this isn’t fleshed out yet. Please stay tuned & stay patient for more content. (Some stuff will be short fiction I promise). Toodles!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mel’s Big Fantasy Place-Name Reference

So I’ve been doing lots of D&D world-building lately and I’ve kind of been putting together lists of words to help inspire new fantasy place names. I figured I’d share. These are helpful for naming towns, regions, landforms, roads, shops, and they’re also probably useful for coming up with surnames. This is LONG. There’s plenty more under the cut including a huge list of “fantasy sounding” word-parts. Enjoy!

Towns & Kingdoms

town, borough, city, hamlet, parish, township, village, villa, domain

kingdom, empire, nation, country, county, city-state, state, province, dominion

Town Name End Words (English flavored)

-ton, -ston, -caster, -dale, -den, -field, -gate, -glen, -ham, -holm, -hurst, -bar, -boro, -by, -cross, -kirk, -meade, -moore, -ville, -wich, -bee, -burg, -cester, -don, -lea, -mer, -rose, -wall, -worth, -berg, -burgh, -chase, -ly, -lin, -mor, -mere, -pool. -port, -stead, -stow, -strath, -side, -way, -berry, -bury, -chester, -haven, -mar, -mont, -ton, -wick, -meet, -heim, -hold, -hall, -point

Buildings & Places

castle, fort, palace, fortress, garrison, lodge, estate, hold, stronghold, tower, watchtower, palace, spire, citadel, bastion, court, manor, house

altar, chapel, abbey, shrine, temple, monastery, cathedral, sanctum, crypt, catacomb, tomb

orchard, arbor, vineyard, farm, farmstead, shire, garden, ranch

plaza, district, quarter, market, courtyard, inn, stables, tavern, blacksmith, forge, mine, mill, quarry, gallows, apothecary, college, bakery, clothier, library, guild house, bath house, pleasure house, brothel, jail, prison, dungeon, cellar, basement, attic, sewer, cistern

lookout, post, tradepost, camp, outpost, hovel, hideaway, lair, nook, watch, roost, respite, retreat, hostel, holdout, redoubt, perch, refuge, haven, alcove, haunt, knell, enclave, station, caravan, exchange, conclave

port, bridge, ferry, harbor, landing, jetty, wharf, berth, footbridge, dam, beacon, lighthouse, marina, dockyard, shipyard

road, street, way, row, lane, trail, corner, crossing, gate, junction, waygate, end, wall, crossroads, barrier, bulwark, blockade, pavilion, avenue, promenade, alley, fork, route

Time & Direction

North, South, East, West, up, down, side, rise, fall, over, under

Winter, Spring, Summer, Autumn, solstice, equanox, vernal, ever, never

dusk, dawn, dawnrise, morning, night, nightfall, evening, sundown, sunbreak, sunset

lunar, solar, sun, moon, star, eclipse

Geographical Terms

Cave, cavern, cenote, precipice, crevasse, crater, maar, chasm, ravine, trench, rift, pit

Cliff, bluff, crag, scarp, outcrop, stack, tor, falls, run, eyrie, aerie

Hill, mountain, volcano, knoll, hillock, downs, barrow, plateau, mesa, butte, pike, peak, mount, summit, horn, knob, pass, ridge, terrace, gap, point, rise, rim, range, view, vista, canyon, hogback, ledge, stair, descent

Valley, gulch, gully, vale, dale, dell, glen, hollow, grotto, gorge, bottoms, basin, knoll, combe

Meadow, grassland, field, pasture, steppe, veld, sward, lea, mead, fell, moor, moorland, heath, croft, paddock, boondock, prairie, acre, strath, heights, mount, belt

Woodlands, woods, forest, bush, bower, arbor, grove, weald, timberland, thicket, bosk, copse, coppice, underbrush, hinterland, park, jungle, rainforest, wilds, frontier, outskirts

Desert, dunes, playa, arroyo, chaparral, karst, salt flats, salt pan, oasis, spring, seep, tar pit, hot springs, fissure, steam vent, geyser, waste, wasteland, badland, brushland, dustbowl, scrubland

Ocean, sea, lake, pond, spring, tarn, mere, sluice, pool, coast, gulf, bay

Lagoon, cay, key, reef, atoll, shoal, tideland, tide flat, swale, cove, sandspit, strand, beach

Snowdrift, snowbank, permafrost, floe, hoar, rime, tundra, fjord, glacier, iceberg

River, stream, creek, brook, tributary, watersmeet, headwater, ford, levee, delta, estuary, firth, strait, narrows, channel, eddy, inlet, rapids, mouth, falls

Wetland, marsh, bog, fen, moor, bayou, glade, swamp, banks, span, wash, march, shallows, mire, morass, quag, quagmire, everglade, slough, lowland, sump, reach

Island, isle, peninsula, isthmus, bight, headland, promontory, cape, pointe, cape

More under the cut including: Color words, Animal/Monster related words, Rocks/Metals/Gems list, Foliage, People groups/types, Weather/Environment/ Elemental words, Man-made Items, Body Parts, Mechanical sounding words, a huge list of both pleasant and unpleasant Atmospheric Descriptors, and a huge list of Fantasy Word-parts.

Color Descriptions

Warm: red, scarlet, crimson, rusty, cerise, carmine, cinnabar, orange, vermillion, ochre, peach, salmon, saffron, yellow, gold, lemon, amber, pink, magenta, maroon, brown, sepia, burgundy, beige, tan, fuchsia, taupe

Cool: green, beryl, jade, evergreen, chartreuse, olive, viridian, celadon, blue, azure, navy, cerulean, turquoise, teal, cyan, cobalt, periwinkle, beryl, purple, violet, indigo, mauve, plum

Neutral: gray, silver, ashy, charcoal, slate, white, pearly, alabaster, ivory, black, ebony, jet

dark, dusky, pale, bleached, blotchy, bold, dappled, lustrous, faded, drab, milky, mottled, opaque, pastel, stained, subtle, ruddy, waxen, tinted, tinged, painted

Animal / Monster-Related Words

Bear, eagle, wolf, serpent, hawk, horse, goat, sheep, bull, raven, crow, dog, stag, rat, boar, lion, hare, owl, crane, goose, swan, otter, frog, toad, moth, bee, wasp, beetle, spider, slug, snail, leech, dragonfly, fish, trout, salmon, bass, crab, shell, dolphin, whale, eel, cod, haddock

Dragon, goblin, giant, wyvern, ghast, siren, lich, hag, ogre, wyrm, kraken

Talon, scale, tusk, hoof, mane, horn, fur, feather, fang, wing, whisker, bristle, paw, tail, beak, claw, web, quill, paw, maw, pelt, haunch, gill, fin,

Hive, honey, nest, burrow, den, hole, wallow

Rocks / Metals / Minerals

Gold, silver, brass, bronze, copper, platinum, iron, steel, tin, mithril, electrum, adamantite, quicksilver, fool’s gold, titanium

Diamond, ruby, emerald, sapphire, topaz, opal, pearl, jade, jasper, onyx, citrine, aquamarine, turquoise, lapiz lazuli, amethyst, quartz, crystal, amber, jewel

Granite, shale, marble, limestone, sandstone, slate, diorite, basalt, rhyolite, obsidian, glass

Earth, stone, clay, sand, silt, salt, mote, lode, vein, ore, ingot, coal, boulder, bedrock, crust, rubble, pebble, gravel, cobble, dust, clod, peat, muck mud, slip, loam, dirt, grit, scree, shard, flint, stalactite/mite

Trees / Plants / Flowers

Tree, ash, aspen, pine, birch, alder, willow, dogwood, oak, maple, walnut, chestnut, cedar, mahogany, palm, beech, hickory, hemlock, cottonwood, hawthorn, sycamore, poplar, cypress, mangrove, elm, fir, spruce, yew

Branch, bough, bramble, gnarl, burr, tangle, thistle, briar, thorn, moss, bark, shrub, undergrowth, overgrowth, root, vine, bracken, reed, driftwood, coral, fern, berry, bamboo, nectar, petal, leaf, seed, clover, grass, grain, trunk, twig, canopy, cactus, weed, mushroom, fungus

Apple, olive, apricot, elderberry, coconut, sugar, rice, wheat, cotton, flax, barley, hops, onion, carrot, turnip, cabbage, squash, pumpkin, pepper

Flower, rose, lavender, lilac, jasmine, jonquil, marigold, carnelian, carnation, goldenrod, sage, wisteria, dahlia, nightshade, lily, daisy, daffodil, columbine, amaranth, crocus, buttercup, foxglove, iris, holly, hydrangea, orchid, snowdrop, hyacinth, tulip, yarrow, magnolia, honeysuckle, belladonna, lily pad, magnolia

People

Settler, Pilgrim, Pioneer, Merchant, Prospector, Maker, Surveyor, Mason, Overseer, Apprentice, Widow, Sailor, Miner, Blacksmith, Butcher, Baker, Brewer, Barkeep, Ferryman, Hangman, Gambler, Fisherman, Adventurer, Hero, Seeker, Hiker, Traveler, Crone

Mage, Magician, Summoner, Sorcerer, Wizard, Conjurer, Necromancer,

King, Queen, Lord, Count, Baron, Guard, Soldier, Knight, Vindicator, Merchant, Crusader, Imperator, Syndicate, Vanguard, Champion, Warden, Victor, Legionnaire, Master, Archer, Footman, Gladiator, Barbarian, Captain, Commodore,

Beggar, Hunter, Ranger, Deadman, Smuggler, Robber, Swindler, Rebel, Bootlegger, Outlaw, Pirate, Brigand, Ruffian, Highwayman, Cutpurse, Thief, Assassin

God, Goddess, Exarch, Angel, Devil, Demon, Cultist, Prophet, Hermit, Seer

council, clergy, guild, militia, choir

Climate, Environment, & The Elements

Cold, cool, brisk, frosty, chilly, icy, freezing, frozen, frigid, glacial, bitter, biting, bleak, arctic, polar, boreal, wintry, snowy, snow, blizzarding, blizzard, sleeting, sleet, chill, frost, ice, icebound, ice cap, floe, snowblind, frostbite, coldsnap, avalanche, snowflake

Hot, sunny, humid, sweltering, steaming, boiling, sizzling, blistering, scalding, smoking, caldescent, dry, parched, arid, fallow, thirsty, melting, molten, fiery, blazing, burning, charring, glowing, searing, scorching, blasted, sun, fire, heat, flame, wildfire, bonfire, inferno, coal, ash, cinder, ember, flare, pyre, tinder, kindling, aflame, alight, ablaze, lava, magma, slag,

Wet, damp, dank, soggy, sodden, soaked, drenched, dripping, sopping, briny, murky, rain, storm, hail, drizzle, sprinkle, downpour, deluge, squall, water, cloud, fog, mist, dew, puddle, pool, current, whirlpool, deep, depths, tide, waves, whitewater, waterfall, tidal wave, flow, flood, leak, drain

Wind, breeze, gust, billow, gail, draft, waft, zephyr, still, airy, clear, smokey, tempest, tempestuous, windswept, aerial, lofty, torrid, turbulent, nebulous, tradewind, thunder, lightning, spark, cyclone, tornado, whirlwind, hurricane, typhoon

Man-made Item Words

Furnace, forge, anvil, vault, strap, strip, whetstone, brick, sword, blade, axe, dagger, shield, buckler, morningstar, bow, quiver, arrow, polearm, flail, staff, stave, sheath, hilt, hammer, knife, helm, mantle, banner, pauldron, chainmail, mace, dart, cutlass, canon, needle, cowl, belt, buckle, bandana, goggles, hood, boot, heel, spindle, spool, thread, sweater, skirt, bonnet, apron, leather, hide, plate, tunic, vest, satin, silk, wool, velvet, lace, corset, stocking, binding

Plow, scythe, (wheel) barrow, saddle, harrow, brand, collar, whip, leash, lead, bridle, stirrup, wheel, straw, stall, barn, hay, bale, pitchfork, well, log, saw, lumber, sod, thatch, mortar, brick, cement, concrete, pitch, pillar, window, fountain, door, cage, spoke, pole, table, bench, plank, board

Candle, torch, cradle, broom, lamp, lantern, clock, bell, lock, hook, trunk, looking glass, spyglass, bottle, vase, locket, locker, key, handle, rope, knot, sack, pocket, pouch, manacle, chain, stake, coffin, fan. cauldron, kettle, pot, bowl, pestle, oven, ladle, spoon, font, wand, potion, elixir, draught, portal, book, tome, scroll, word, manuscript, letter, message, grimoire, map, ink, quill, pen, cards, dice

Coin, coronet, crown, circlet, scepter, treasure, riches, scales, pie, tart, loaf, biscuit, custard, caramel, pudding, porridge, stew, bread, tea, gravy, gristle, spice, lute, lyre, harp, drum, rouge, powder, perfume, brush

bilge, stern, pier, sail, anchor, mast, dock, deck, flag, ship, boat, canoe, barge, wagon, sled, carriage, buggy, cart

Wine, brandy, whiskey, ale, moonshine, gin, cider, rum, grog, beer, brew, goblet, flagon, flask, cask, tankard, stein, mug, barrel, stock, wort, malt

Body Parts

Head, throat, finger, foot, hand, neck, shoulder, rib, jaw, eye, lips, bosom

Skull, spine, bone, tooth, heart, blood, tears, gut, beard

Mechanical-Sounding Words

cog, fuse, sprocket, wrench, screw, nail, bolt, lever, pulley, spanner, gear, spring, shaft, switch, button, cast, pipe, plug, dial, meter, nozzle, cord, brake, gauge, coil, oil, signal, wire, fluke, staple, clamp, bolt, nut, bulb, patch, pump, cable, socket

torque, force, sonic, spark, fizzle, thermal, beam, laser, steam, buzz, mega, mecha, electro, telsa, power, flicker, charge, current, flow, tinker

Atmospheric Words

Unpleasant, Dangerous, Threatening

(nouns) death, fury, battle, scar, shadow, razor, nightmare, wrath, bone, splinter, peril, war, riptide, strife, reckoning, sorrow, terror, deadwood, nether, venom, grime, rage, void, conquest, pain, folly, revenge, horrid, mirk, shear, fathom, frenzy, corpselight/marshlight, reaper, gloom, doom, torment, torture, spite, grizzled, sludge, refuse, spore, carrion, fear, pyre, funeral, shade, beast, witch, grip, legion, downfall, ruin, plague, woe, bane, horde, acid, fell, grief, corpse, mildew, mold, miter, dirge

(adjectives) dead, jagged, decrepit, fallen, darkened, blackened, dire, grim, feral, wild, broken, desolate, mad, lost, under, stagnant, blistered, derelict, forlorn, unbound, sunken, fallow, shriveled, wayward, bleak, low, weathered, fungal, last, brittle, sleepy, -strewn, dusky, deserted, empty, barren, vacant, forsaken, bare, bereft, stranded, solitary, abandoned, discarded, forgotten, deep, abysmal, bottomless, buried, fathomless,unfathomable, diseased, plagued, virulent, noxious, venomous, toxic, fetid, revolting, putrid, rancid, foul, squalid, sullied, vile, blighted, vicious, ferocious, dangerous, savage, cavernous, vast, yawning, chasmal, echoing, dim, dingy, gloomy, inky, lurid, shaded, shadowy, somber, sunless, tenebrous, unlit, veiled, hellish, accursed, sulfurous, damned, infernal, condemned, doomed, wicked, sinister, dread, unending, spectral, ghostly, haunted, eldritch, unknown, weary, silent, hungry, cloven, acidic

(verb/adverbs): wither (withering / withered), skulk (skulking), whisper, skitter, chitter, sting, slither, writhe, gape, screech, scream, howl, lurk, roil, twist, shift, swarm, spawn, fester, bleed, howl, shudder, shrivel, devour, swirl, maul, trip, smother, weep, shatter, ruin, curse, ravage, hush, rot, drown, sunder, blister, warp, fracture, die, shroud, fall, surge, shiver, roar, thunder, smolder, break, silt, slide, lash, mourn, crush, wail, decay, crumble, erode, decline, reek, lament, taint, corrupt, defile, poison, infect, shun, sigh, sever, crawl, starve, grind, cut, wound, bruise, maim, stab, bludgeon, rust, mutilate, tremble, stumble, fumble, clank, clang

Pleasant, Safe, Neutral

(nouns) spirit, luck, soul, oracle, song, sky, smile, rune, obelisk, cloud, timber, valor, triumph, rest, dream, thrall, might, valiance, glory, mirror, life, hope, oath, serenity, sojourn, god, hearth, crown, throne, crest, guard, rise, ascent, circle, ring, twin, vigil, breath, new, whistle, grasp, snap, fringe, threshold, arch, cleft, bend, home, fruit, wilds, echo, moonlight, sunlight, starlight, splendor, vigilance, honor, memory, fortune, aurora, paradise, caress

(adjectives) gentle, pleasant, prosperous, peaceful, sweet, good, great, mild, grand, topic, lush, wild, abundant, verdant, sylvan, vital, florid, bosky, callow, verdurous, lucious, fertile, spellbound, captivating, mystical, hidden, arcane, clandestine, esoteric, covert, cryptic, runic, otherworldly, touched, still, fair, deep, quiet, bright, sheer, tranquil, ancient, light, far, -wrought, tidal, royal, shaded, swift, true, free, high, vibrant, pure, argent, hibernal, ascendant, halcyon, silken, bountiful, gilded, colossal, massive, stout, elder, -bourne, furrowed, happy, merry, -bound, loud, lit, silk, quiet, bright, luminous, shining, burnished, glossy, brilliant, lambent, lucent, lustrous, radiant, resplendent, vivid, vibrant, illuminated, silvery, limpid, sunlit, divine, sacred, holy, eternal, celestial, spiritual, almighty, anointed, consecrated, exalted, hallowed, sanctified, ambrosial, beatific, blissful, demure, naked, bare, ample, coy, deific, godly, omnipotent, omnipresent, rapturous, sacramental, sacrosanct, blessed, majestic, iridescent, glowing, overgrown, dense, hard, timeless, sly, scatter, everlasting, full, half, first, last

(verb/adverbs) arch (arching / arched), wink (winking), sing, nestle, graze, stroll, roll, flourish, bloom, bud, burgeon, live, dawn, hide, dawn, run, pray, wake, laugh, wake, glimmer, glitter, drift, sleep, tumble, bind, arch, blush, grin, glister, beam, meander, wind, widen, charm, bewitch, enthrall, entrance, enchant, allure, beguile, glitter, shimmer, sparkle twinkle, crest, quiver, slumber, herald, shelter, leap, click, climb, scuttle, dig, barter, chant, hum, chime, kiss, flirt, tempt, tease, play, seduce

Generic “Fantasy-Sounding” Word Parts

A - D

aaz, ada, adaer, adal, adar, adbar, adir, ae, ael, aer, aern, aeron, aeryeon, agar, agis, aglar, agron, ahar, akan, akyl, al, alam, alan, alaor, ald, alea, ali, alir, allyn, alm, alon, alor, altar, altum, aluar, alys, amar, amaz, ame, ammen, amir, amol, amn, amus, anar, andor, ang, ankh, ar, ara, aram, arc, arg, arian, arkh, arla, arlith, arn, arond, arthus, arum, arvien, ary, asha, ashyr, ask, assur, aster, astra, ath, athor, athra, athryn, atol, au, auga, aum, auroch, aven, az, azar, baal, bae, bael, bak, bal, balor, ban, bar, bara, barr, batol, batar, basir, basha, batyr, bel, belph, belu, ben, beo, bere, berren, berun, besil, bezan, bhaer, bhal, blask, blis, blod, bor, boraz, bos, bran, brath, braun, breon, bri, bry, bul, bur, byl, caer, cal, calan, cara, cassa, cath, cela, cen, cenar, cerul, chalar, cham, chion, cimar, clo, coram, corel, corman, crim, crom, daar, dach, dae, dago, dagol, dahar, dala, dalar, dalin, dam, danas, daneth, dannar, dar, darian, darath, darm, darma, darro, das, dasa, dasha, dath, del, delia, delimm, dellyn, delmar, delo, den, dess, dever, dhaer, dhas, dhaz, dhed, dhin, din, dine, diar, dien, div, djer, dlyn, dol, dolan, doon, dora, doril, doun, dral, dranor, drasil, dren, drian, drien, drin, drov, druar, drud, duald, duatha, duir, dul, dulth, dun, durth, dyra, dyver,

E - H

ea, eber, eden, edluk, egan, eiel, eilean, ejen, elath, eld, eldor, eldra, elith emar, ellesar, eltar, eltaran, elth, eltur, elyth, emen, empra, emril, emvor, ena, endra, enthor, erad, erai, ere, eriel, erith, erl, eron, erre, eryn, esk, esmel, espar, estria, eta, ethel, eval, ezro, ezan, ezune, ezil, fael, faelar, faern, falk, falak, farak, faril, farla, fel, fen, fenris, fer, fet, fin, finar, forel, folgun, ful, fulk, fur, fyra, fallon, gael, gach, gabir, gadath, gal, galar, gana, gar, garth, garon, garok, garne, gath, geir, gelden, geren, geron, ghal, ghallar, ghast, ghel, ghom, ghon, gith, glae, glander, glar, glym, gol, goll, gollo, goloth, gorot, gost, goth, graeve, gran, grimm, grist, grom, grosh, grun, grym, gual, guil, guir, gulth, gulur, gur, gurnth, gwaer, haa, hael, haer, hadar, hadel, hakla, hala, hald, halana, halid, hallar, halon, halrua, halus, halvan, hamar, hanar, hanyl, haor, hara, haren, haresk, harmun, harrokh, harrow, haspur, haza, hazuth, heber, hela, helve, hem, hen, herath, hesper, heth, hethar, hind, hisari, hjaa, hlath, hlond, hluth, hoarth, holtar, horo, hotun, hrag, hrakh, hroth, hull, hyak, hyrza

I - M

iibra, ilth, ilus, ilira, iman, imar, imas, imb, imir, immer, immil, imne, impil, ingdal, innar, ir, iriae, iril, irith, irk, irul, isha, istis, isil, itala, ith, ithal, itka, jada, jae, jaeda, jahaka, jala, jarra, jaro, jath, jenda, jhaamm, jhothm, jinn, jinth, jyn, kado, kah, kal, kalif, kam, kana, kara, karg, kars, karth, kasp, katla, kaul, kazar, kazr, kela, kelem, kerym, keth, keva, kez, kezan, khaer, khal, khama, khaz, khara, khed, khel, khol, khur, kil, kor, korvan, koll, kos, kir, kra, kul, kulda, kund, kyne, lae, laen, lag, lan, lann, lanar, lantar, lapal, lar, laran, lareth, lark, lath, lauth, lav, lavur, lazar, leih, leshyr, leth, lhaza, lhuven, liad, liam, liard, lim, lin, lirn, lisk, listra, lith, liya, llair, llor, lok, lolth, loran, lorkh, lorn, loth, lothen, luen, luir, luk, lund, lur, luth, lyndus, lyra, lyth, maal, madrasm maera, maer, maerim, maes, mag, magra, mahand, mal, malar, mald, maldo, mar, mara, mark, marl, maru, maruk, meir, melish, memnon, mer, metar, methi, mhil, mina, mir, miram, mirk, mista, mith, moander, mok, modir, modan, mon, monn, mor, more, morel, moril, morn, moro, morrow, morth, mort, morum, morven, muar, mul, mydra, myr, myra, myst

N - S

naar, nadyra, naedyr, naga, najar, nal, naal, nalir, nar, naruk, narbond, narlith, narzul, nasaq, nashkel, natar, nath, natha, neir, neth, nether, nhall, nikh, nil, nilith, noan, nolvurm nonthal, norda, noro, novul, nul, nur, nus, nyan, nyth, ober, odra, oghr, okoth, olleth, olodel, omgar, ondath, onthril, ordul, orish, oroch, orgra, orlim, ormath, ornar, orntath, oroch, orth, orva, oryn, orzo, ostel, ostor, ostrav, othea, ovar, ozod, ozul, palan, palad, pae, peldan, pern, perris, perim, pele, pen, phail, phanda, phara, phen, phendra, pila, pinn, pora, puril, pur, pyra, qadim, quar, quel, ques, quil, raah, rael, ran, ranna, rassil, rak, rald, rassa, reddan, reith, relur, ren, rendril, resil, reska, reth, reven, revar, rhy, rhynn, ria, rian, rin, ris, rissian, rona, roch, rorn, rora, rotha, rual, ruar, ruhal, ruil, ruk, runn, rusk, ryn, saa, saar, saal, sabal, samar, samrin, sankh, sar, sarg, sarguth, sarin, sarlan, sel, seld, sember, semkh, sen, sendrin, septa, senta, seros, shaar, shad, shadra, shae, shaen, shaera, shak, shalan, sham, shamath, shan, shana, sharan, shayl, shemar, shere, shor, shul, shyll, shyr, sidur, sil, silvan, sim, sintar, sirem, skar, skell, skur, skyr, sokol, solan, sola, somra, sor, ssin, stel, strill, suldan, sulk, sunda, sur, surkh, suth, syl, sylph, sylune, syndra, syth

T - Z

taak, taar, taer, tah, tak, tala, talag, talar, talas, talath, tammar, tanar, tanil, tar, tara, taran, tarl, tarn, tasha, tath, tavil, telar, teld, telf, telos, tempe, tethy, tezir, thaar, thaer, thal, thalag, thalas, thalan, thalar, thamor, thander, thangol, thar, thay, thazal, theer, theim, thelon, thera, thendi, theril, thiir, thil, thild, thimir, thommar, thon, thoon, thor, thran, thrann, threl, thril, thrul, thryn, thuk, thultan, thume, thun, thy, thyn, thyr, tir, tiras, tirum, tohre, tol, tolar, tolir, tolzrin, tor, tormel, tormir, traal, triel, trith, tsath, tsur, tul, tur, turiver, turth, tymor, tyr, uder, udar, ugoth, uhr, ukh, ukir, uker, usten, ulgarth, ulgoth, ultir, ulur, umar, umath, umber, unara, undro, undu, untha, upir, ur, ursa, ursol, uron, uth, uthen, uz, van, vaar, vaelan, vaer, vaern, val valan, valash, vali, valt, vandan, vanede, vanrak, var, varyth, vassa, vastar, vaunt, vay, vel, velar, velen, velius, vell, velta, ven, veren, vern, vesper, vilar, vilhon, vintor, vir, vira, virdin, volo, volun, von, voon, vor, voro, vos, vosir, vosal, vund, war, wara, whel, wol, wynn, wyr, wyrm, xer, xul, xen, xian, yad, yag, yal, yar, yath, yeon, yhal, yir, yirar, yuir, yul, yur, zail, zala, zalhar, zan, zanda, zar, zalar, zarach, zaru, zash, zashu, zemur, zhent, zim, ziram, zindala, zindar, zoun, zul, zurr, zuth, zuu, zym

A lot of places are named after historical events, battles, and people, so keep that in mind. God/Goddess names tied to your world also work well. Places are also often named after things that the area is known for, like Georgia being known for its peaches.

My brain was fried by the end of this so feel free to add more!

I hope you find this reference helpful and good luck world-building!

-Mel

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Since moving to Fidalgo Island last July I’ve immersed myself in my immediate surroundings: the park, town and shoreline locations that are minutes from home. We are a long 90 miles (145km) from the ocean, but it’s still a water-defined landscape; Fidalgo’s shores look out onto sounds, bays, channels, and more islands, and even the forests here are dotted with lakes.

If you head east off the island, it’s a very different landscape. As you mount a high, arcing bridge, overlapping layers of foothills and mountains appear in the distance. Agricultural flatlands spread out on either side of the road, to the north and south. The view ahead steals the show as rhythmic mounds of forested hills rise up and gradually crumple into the jagged, rocky folds of the North Cascade Range. That rough and rugged terrain was beckoning me a few months ago – but I’m no mountaineer, so on a quiet Tuesday in October, we headed east for a lowland walk in the Mount Baker – Snoqualmie National forest.

1. Baker River Trail/East Bank Baker Lake Trail.

The goal was to meander along the East Bank Baker Lake Trail, an easy walk through the thick, coniferous forest that Baker River passes through as it divides into countless turquoise ribbons, braiding their way towards Baker Lake. The river’s namesake, Mt. Baker, or Koma Kulshan, is a young, glaciated volcano, and the third-highest mountain in the state, at 10,781 ft. (3286 m). Koma Kulshan’s lofty, somber face dominates many a vista in this region. You might think Baker River begins under a glacier on Mt. Baker, but it actually rises under Whatcom Peak, to the northeast. From there, the river cuts a deep valley southwest, flowing around Mt. Baker before emptying into Baker Lake.

2. After a dry summer, the river is a series of shallow ribbons of cold water, unfurling over a rocky bed.

Getting to the trail was harder than we thought it would be. The first part was simple – drive east past fields and small towns on State Route 20. Then, in the tiny hamlet of Birdsview, you leave civilization behind to follow Baker Lake Road for 26 miles (42 km). The problem was the final six miles, where the road is not paved, and barely maintained. We still have the cars we brought with us from New York City seven years ago, and neither one is appropriate for the rough, deeply pot-holed forest roads that usually lead to trailheads. It’s really a pickup truck, SUV and Subaru world here. The going was tedious as we crawled back and forth across the road, trying not to wreck the car’s suspension. Occasional glimpses of snowy Mt. Baker beckoned through dense curtains of towering trees, and eventually the painfully slow slog ended.

3. The paved section of Baker Lake Road.

4. The road narrows and begins to get rough while Mount Baker looms majestically above us.

5. An old Redcedar leans heavily over the trail.

6. This beautifully built suspension bridge puts a little bounce into your step, like it or not.

7. We saw thousands of small moths that day, both alive and dead. This one came to rest on a Redcedar bough. Shining drops of morning dew still cling to the delicate wings and body.

8. This little one was alive, but maybe not for long.

9. A dew-spangled dead moth is cradled in the leaf litter.

10. Another rough-hewn wooden bridge on the trail crosses one of many creeks feeding Baker River. The rustic bridges are a real pleasure to see, to touch, and to walk across.

11. I have great respect for the people who built these bridges.

Water and rocks, from the bridge.

Light plays across the rocks in shallow water.

13. The bridge views were mesmerizing. Baker River rippled past water-sculpted rocks and the light danced over smooth stones that were barely covered by the shallow water.

14. Looking up river it’s easy to picture how, after a winter of heavy snow in the mountains, the river fills up with glacial melt and roars down towards Baker Lake, taking fallen trees along for the ride, only to abandon the logs in untidy clumps, as the flow dwindles over the summer.

15. Bigleaf maples had dropped their leaves in layers of nourishing mulch – in the woods, on the trail, and on the road, too.

16. Mushrooms crowded this stump like a Hong Kong high rise.

17. A fresh mushroom bouquet decorated with sprays of Licorice fern.

18. This handsome specimen emerged from thick moss on the moist forest floor.

19. Forest floor synergy could be seen at our feet: rotting logs, fallen leaves and twigs, moss, mushrooms, and so much more that we didn’t see, all working together to support life.

20. A hiker stops to admire an old growth Redcedar pressing against huge boulder covered with moss, lichens and ferns.

21. Constant moisture from the river nearby means that in this part of the forest, every dead limb wears a luxurious coat of spongy moss, all year long.

22. Feathery-boughed cedars with their tapered trunks and waving, mossy branches made an enchanted forest scene. Green never departs from this forest, it just waxes and wanes in intensity.

23. Cedar bark invites a close look, especially when the tree sports a stripe of bright green lichen. Look closely and you’ll see other lichens here, too.

24. The drab but pert American Dipper is always a thrill to see. This little bundle of energy forages by dipping, walking and even swimming in the rushing water of tumbling streams. When perched, dippers constantly bounce up and down, and movement is about all that gives them away, since the plain gray birds are hard to see among dark boulders, fallen trees, and the noisy, rushing water.

25. The days were getting shorter and we had a late start that day, so we turned back to avoid driving 26 miles in darkness.

26. Low-angled sun silvered the meandering river.

27. As we were about to get into the car, I noticed a maple leaf caught on a twig and made one more photograph. There’s always one more….

If you’re in the area:

The East Bank Baker Lake and Baker River Trails are about 115 (185km) miles from Seattle, and about 124 miles (200km) from Vancouver, BC. The trailhead is 64 rather slow miles from where I live. Once you arrive at the large parking lot, if it’s an off-season weekday, you may be all alone. Set out on the wide, flat trail among huge boulders and towering trees, and soon you’ll sense the river behind the trees. In half a mile a suspension bridge crosses the river. From there, the Baker Lake Trail continues down the river and then follows the lake edge, for a total of 14.5 miles one way. Along the trail you’ll find more bridges, and views of the snow-covered mountains high above that are the repositories for all this rushing water. If you don’t cross the first bridge you can continue straight upriver on the Baker River Trail, reaching a campground in 2.6 miles. It was so pleasant the day we were there, and there was so much to look at, that we didn’t get far at all. That was not the object. The point was to feel, hear, see, and smell this unique place, to fully sense the aliveness of one small corner of our planet.

A Little Farther Into the Woods Since moving to Fidalgo Island last July I've immersed myself in my immediate surroundings: the park, town and shoreline locations that are minutes from home.

0 notes

Text

News reports and interesting up-dates on POS Hardware and POS.

Every Juneteenth, as soon as Pamela Baker got to Booker T. Washington Park, she’d race to the merry-go-round, squeeze through the swarm of shrieking kids, grab one of the shiny rails, and hold on tight. After a few minutes, she would jump off and dart up the steps of the nearby dance hall to survey the throngs below. She and her brother Carl would weave through the crowd, looking for cousins from Dallas and Houston they hadn’t seen since the previous year. Eventually, her whole family would congregate under an oak tree their ancestors had claimed as a gathering place a century before, in the years after news of the end of slavery reached Texas.

“Every year, this is where we’d be,” Baker said. It was a cold January day, and she sat in a purple pew in the park’s open-air tabernacle. Baker, sixty, wore camo pants, a hoodie, and a knit cap. She had come from work and looked tired as a heavy rain beat down around her. The park sits along Lake Mexia (pronounced “muh-hay-ah”), about thirty miles east of Waco. For generations, African Americans made pilgrimages to this spot to celebrate Juneteenth, or Emancipation Day. They came from all over the country to hear the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, to worship, to run and play in the green fields, to dance in the creaky pavilion, to eat barbecue and drink red soda water, to sleep under the stars. Locals referred to the park by its name from an earlier time: Comanche Crossing. Juneteenth here would run for days on end. It was like a giant family reunion, held on hallowed ground.

The merry-go-round at the park on April 21, 2021.Photograph by Michael Starghill

Baker grew up in nearby Mexia, and each June, her family would camp around that same towering oak. In the early sixties her grandfather built a wooden countertop around the trunk, and every June 19, her grandmother and members of her grandmother’s social club would fry scores of chickens in an old black washpot—enough to serve a few hundred people who’d stop by to sit, eat, and reminisce. “Juneteenth meant everything to us,” Baker said. As a kid, she looked forward to the holiday all year long.

Until she didn’t.

“After what happened with my brother,” she said, “we weren’t interested in coming out here anymore.”

Forty years ago, on June 19, 1981, not far from where she sat now, her brother Carl and two other Black teenagers drowned while in the custody of a Limestone County sheriff’s deputy, a reserve deputy, and a probation officer. The Baker family was devastated—as was the entire town of Mexia. The deaths became national news, with people from New York to California asking the same question as those in Central Texas: Why had three Black teens died while all three officers—two of them white, one Black—survived?

Over the years, whenever a highly publicized incident of police brutality against a Black person occurred, many in Mexia would think back to that night in 1981. This was never more true than last summer, when outrage at George Floyd’s murder, captured on video in broad daylight, sparked one of the largest protest movements in U.S. history. As millions of demonstrators took to the streets, Mexia residents were reminded of the drownings that once rocked their community and forever changed their hometown’s proud Juneteenth celebration, which had been among the nation’s most historic.

Four decades later, Baker still grieves for her brother. “It never goes away,” she said quietly, sitting in the pew, surrounded by the ghosts of her ancestors. “I miss everything about Carl—just seeing his smile, his dark skin with beautiful white teeth, walk into the house after work. I wish I could see him come up out of the water right now, but I know I can’t.”

She paused and looked toward the lake. “My brother,” she said, “he didn’t deserve that, what they did to him.”

Pamela Baker sitting in the park tabernacle on April 21, 2021.Photograph by Michael Starghill

James Ferrell was at Comanche Crossing on June 19, 1981. It was a clear, warm Friday night, and Ferrell, a tall 34-year-old who sported a scruffy beard and a cowboy hat, had led a trail ride to the park from nearby Sandy. He sat with his brothers, cousins, friends, and their horses, drinking beer, telling stories, laughing. They could hear music coming from the pavilion and see a line of cars creeping over the bridge onto the grounds, while pedestrians who had parked two miles away on U.S. 84 hiked through the gridlock. The moon was almost full, and the air smelled of grilled burgers, fried fish, and popcorn.

Sometime after ten, three law enforcement officers clambered into a boat on the other side of the lake and pushed off. Lake Mexia is a shallow, dammed stretch of the Navasota River in the shape of an M; the park sits near the lake’s center, where the water is about two hundred yards across. The Limestone County Sheriff’s Office had set up a command post on the opposite bank. The deputies rarely patrolled the park after sundown, but on this night they did. Because the bridge was bottlenecked, they cut across the lake in a fourteen-foot aluminum vessel. They were led by sheriff’s deputy Kenny Elliott, 23, who’d been on the force for about a year. The Black officer, reserve deputy Kenneth Archie, was also 23 and a former high school basketball player from Houston. The third man was David Drummond, a 32-year-old probation officer who planned to check on some of his parolees.

The boat hit the shore, and the men climbed onto the bank, which was muddy from recent rains. Though the three officers wore street clothes, they stuck out in the nearly all-Black crowd of roughly five thousand. “Police have a special way of walking,” recalled one bystander. They stopped at the concession stands to buy some soft drinks, then moved on. Young lovers walked through the crowd, eating cotton candy. Elderly men and women, many wearing their Sunday best, perched on benches talking to old friends. Everywhere the officers walked, they saw tents and campers with families gathered around. Some folks were dozing, some were playing dominoes, some were drinking beer or whiskey. Some were smoking marijuana, and as the officers passed, they either snuffed out their joints or hid them behind their backs. “When they came up,” Ferrell said, “we just put it down. They never said nothing. They walked off.”

As the trio approached one of the park’s small caliche roads, they came upon a yellow Chevrolet Nova stuck in traffic. Inside were four local teenagers: Carl Baker, Steve Booker, Jay Wallace, and Anthony Freeman, whom friends called “Rerun” because he resembled the hefty character from the sitcom What’s Happening!! As Elliott shone his flashlight through the windshield, he saw the teens passing a small plastic bag of what he took to be marijuana. It was just after eleven, and in the time since he’d crossed the lake, Elliott hadn’t acknowledged similar violations of the law. Now, though, the deputy ordered the four out of the car and made them put their hands on the roof while the officers patted them down and searched the interior.

A bridge over Lake Mexia.Photograph by Michael Starghill

They found the baggie of weed and a joint, which they confiscated. Wallace would later say that the officers “didn’t act like they knew what they was doing; they kept asking each other what they should do.” The crowd began to take notice. As far as anyone could remember, there had never been an arrest at the park during Juneteenth festivities.

Elliott made the decision to take Baker, Freeman, and Booker into custody. Days later, Wallace would tell the Waco Tribune-Herald that the officers found drugs on Baker and Booker, while Freeman was arrested because the car belonged to him. Wallace was spared because “they didn’t find anything on me.”

At least two and possibly all three of the teens were handcuffed; some witnesses said Baker and Booker were cuffed together, while others recalled each being restrained individually. Onlookers didn’t like what they saw, and some began to curse at the officers. Rather than walk the teens through the crowd, over the bridge, and around the lake, the officers opted to go back the way they came.

When the group reached the boat, Elliott climbed into the back by the motor. Next were Booker and Baker, then Drummond and Freeman. Archie, who weighed more than two hundred pounds, sat in the bow. There were no life jackets, and the combined weight of the passengers exceeded the boat’s capacity by several hundred pounds.

Elliott started the motor. The craft had no running lights, and as it crept forward, water started pouring in. Drummond yelled back to Elliott, who couldn’t hear him over the engine; Drummond yelled again, and this time Elliott turned it off. By then, they had traveled about forty yards. As the boat slowed, more water rushed in, and the craft submerged and flipped over. All six began splashing wildly in the ten-foot-deep water.

Elliott shouted for the others to stay with the boat while he swam to shore for help. As soon as he reached water shallow enough to stand in, he fired his gun into the air, in what he would later say was an attempt to summon assistance. Soon after, he was joined by Drummond. Out on the water, Archie, who wasn’t a good swimmer, clung to the boat “like a spider,” one witness said.

The teens were nowhere in sight.

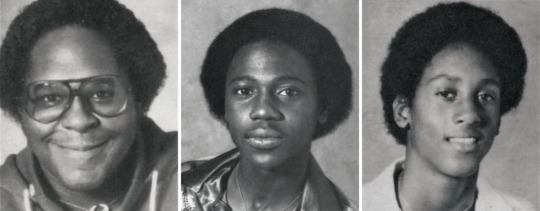

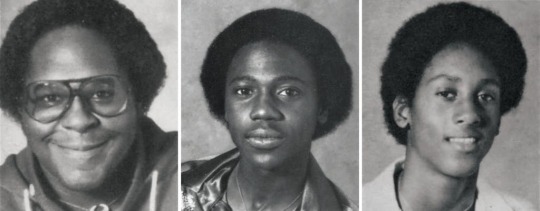

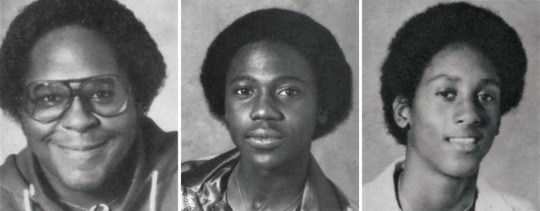

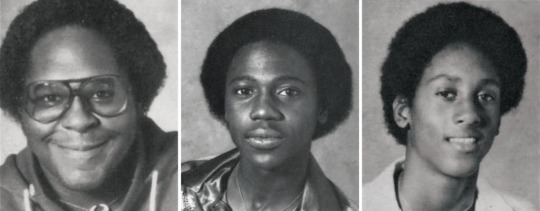

Mexia High School yearbook photos of Anthony Freeman, Carl Baker, and Steve Booker.Gibbs Memorial Library

While a boater pulled Archie out of the water, Elliott and Drummond ran across the bridge to the command post to report what had happened. Someone called the fire department, and before long a search party was on the lake. As campers watched from the shore, firefighters in three boats threw dredging hooks into the water. Onlookers hoped against hope that the teens had been able to swim to safety.

Around 2 a.m., the crowd’s worst fears were realized. A body was found near the bridge, tangled in a trotline. An observer, David Echols, said the rescuers positioned their boats between the body and the civilians and spent twenty minutes pulling it out. “They were shielding the bank where we couldn’t see.”

The body was Baker’s. The searchers brought him back to shore, where they took a couple of hours to regroup before returning to the lake at dawn. All the while, Juneteenth campers kept watch. Mexia was a small town where just about everybody knew Baker, Freeman, and Booker. They were country boys who had grown up playing at the local pool and in this very lake, although Freeman was scared of water, and his mother said he “couldn’t swim, not one lick.” Baker and Booker, however, were known to be excellent swimmers. “Carl was like Mark Spitz,” said his friend Rick Washington. “He could dive in the pool and swim underwater and come up at the other end.”

“Carl was like Mark Spitz,” said his friend Rick Washington. “He could dive in the pool and swim underwater and come up at the other end.”

How could Elliott, Archie, and Drummond survive while all three teens were presumed lost? Many witnesses had seen the teenagers marched through the crowd with handcuffs on. Had the handcuffs stayed on in the boat?

About 1:30 p.m., another body was found near the bridge. Three rescue boats formed a circle around it, blocking observers from making out the crew’s actions. “They took a while before they pulled the body out,” said a reporter who covered the search, “but we couldn’t see what they were doing.” What they were doing was retrieving Freeman’s body from the water.

The apparent secrecy fueled more suspicions, which intensified as the search for Booker continued. The next day, his body floated to the surface not far from where the others had been found. By then, many in Mexia who’d heard about the drownings believed that the teens had been handcuffed when the boat flipped. A hot-dog vendor named Arthur Beachum Jr. told a reporter about seeing Baker being removed from the water. “I saw them pull the body from the lake and it still had handcuffs on it. One officer took them off and put them in his pocket.”

Sheriff Dennis Walker denied this to the press. “It was a freak accident,” he said. “All of what they’re saying is untrue.” Reserve deputy Archie told a reporter that two of the teens had been handcuffed together but that the cuffs had been removed before Baker, Booker, and Freeman were led into the boat. According to the Dallas Times Herald, Archie also said that if he’d been in charge, things would have been different: “I probably would’ve pulled the marijuana out and put it in the mud puddle next to the car and sent the suspects on their way.” (He later denied saying this.) Sheriff Walker said, “This could turn out to be a racial-type deal.”

That was an understatement. Reporters and TV crews from Waco, Fort Worth, Dallas, and Houston arrived in Mexia. By Sunday, the drownings were national news. “Youths Allegedly Handcuffed,” read a headline in the New York Times. The NAACP sent a team of investigators and demanded the Department of Justice conduct an inquiry. Someone from the DOJ called the sheriff on Monday morning and was given directions to the sheriff’s headquarters in Groesbeck, the county seat. The FBI came too.

Richard Dockery, the head of the Dallas NAACP, examined Baker’s body and told reporters he thought that the position of the young man’s hands—wrists together, fingers curled—meant he had been cuffed. Initial autopsies of Baker and Freeman, done in Waco, found no bruising or signs of struggle, prompting Booker’s mother to announce she was taking her son’s body to Dallas because she wouldn’t get “anything but lies” from Waco pathologists.

Reporters rang the sheriff around the clock, and Walker later complained that the attention “severely hampered” his investigation. “The press has been calling me day and night from as far away as Chicago and New York,” he said. “I had to leave the house to get a couple of hours of rest.” Mexia’s mayor called the coverage “sensationalized,” while many white townspeople felt torn between defending their home against its portrayal as a racist backwater and acknowledging the wrong that had been done. “I was at a laundromat yesterday,” a white waitress told a reporter from Fort Worth, “and usually everyone gets along alright, but yesterday some of the Blacks were kind of testy . . . and I don’t blame them.”

The drownings had exposed a deep rift in Mexia, one that went back generations and couldn’t be smoothed over. “My God, this has turned the whole town upside down,” a local man told the Waco Tribune-Herald, “and those three boys ain’t even in the ground yet.”

The pavilion and tabernacle at Booker T. Washington Park on April 21, 2021.Photograph by Michael Starghill

Rick Washington was in the Navy in June 1981, stationed aboard the U.S.S. Tuscaloosa in the Philippines, when a shipmate handed him a newspaper. “Wash,” he said, “ain’t this where you’re from? M-e-x-i-a, Texas?” Washington, then twenty, read the headline about a triple drowning. Then he saw the names. “I just broke down like a twelve-gauge shotgun. Steve, Carl, Rerun. They were my best friends.”

Now sixty, Washington is the pastor at Mexia’s Greater Little Zion Baptist Church, and every day he drives past places where he and his friends used to play. “We would eat breakfast, leave home, come home for lunch, leave again, be home before the streetlights came on,” Washington said. “We were almost never inside.” They would ride bikes, play football and basketball, hunt rabbits, swim at the city pool, and explore the rolling, scrubby plains.

Washington, like everyone else in Mexia who knew Baker, Freeman, and Booker, remembered them as typical small-town teenagers. Baker was short, handsome, and athletic. He liked hanging out at the pool—he was such a good swimmer that the lifeguards sometimes asked him to help out when it got busy. He’d graduated from Mexia High School the previous year and was working at a local cotton gin. He was nineteen, with an easy charm and a voluminous Afro that had taken months to grow out.

Anthony Freeman, the youngest of the three at eighteen, was an only child of strict parents. He played piano, performing every week at the church his family attended. “He was a very bright kid,” said Shree Steen-Medlock, who went to high school with Freeman. “I remember him trying to fit in and not be the nerdy kind of guy.” He had graduated that spring, and he and Baker planned on going to Paul Quinn College, then in Waco, in the fall.

Nineteen-year-old Steve Booker was the group’s extrovert. “He was flamboyant, like Deion Sanders,” said his friend John Proctor. Booker was born in Dallas and raised on his grandparents’ farm in Mexia, where he helped to pen cattle, feed hogs, and mend fences. He loved basketball and grew up shooting on a hoop and backboard made out of a bicycle wheel and a sheet of plywood. Once, playing for Mexia High’s JV team, he hit a game-winner from half-court. In 1980 Booker moved back to Dallas, where he graduated high school and found work at a detergent supply company, but he’d returned that week to celebrate Juneteenth.

The Mexia where the three grew up was a tight-knit city of roughly seven thousand, about a third of whom were Black. Kids left their bikes on the lawn, families left their doors unlocked, and horses and cattle grazed in pastures on the outskirts of town. Boys played Little League, and everybody went to church. Mexia was known as the place near Waco with the odd name (which it got from the Mexía family, who received a large land grant in the area in 1833). City leaders came up with a perfect slogan: “Mexia . . . a great place to live . . . however you pronounce it.” Football fans might have heard that NFL player Ray Rhodes grew up there; country music fans knew Mexia as the home base of famed songwriter Cindy Walker.

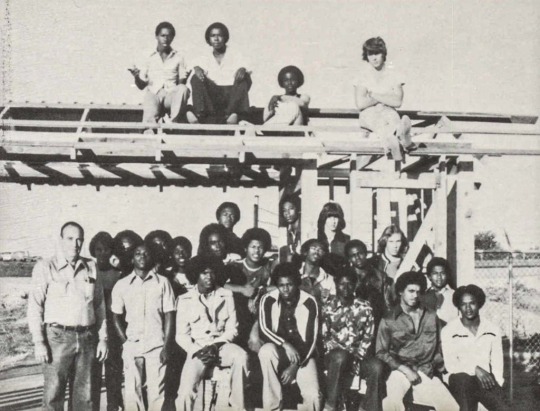

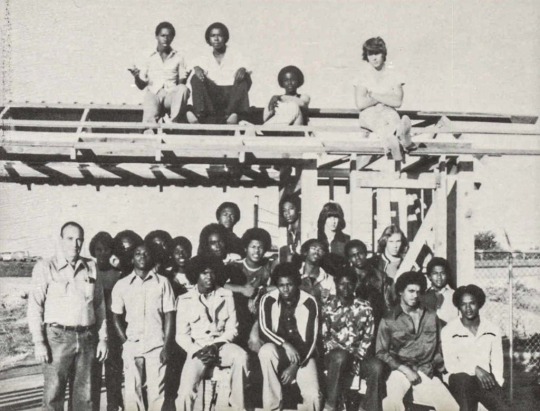

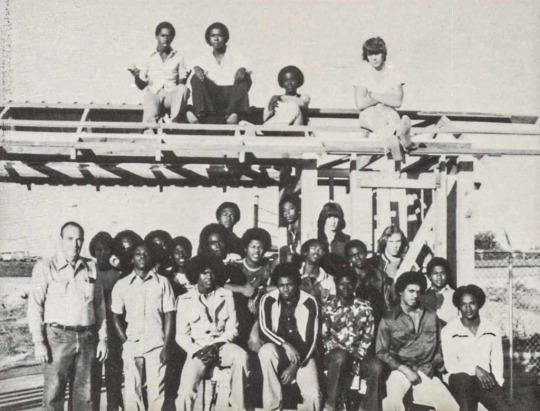

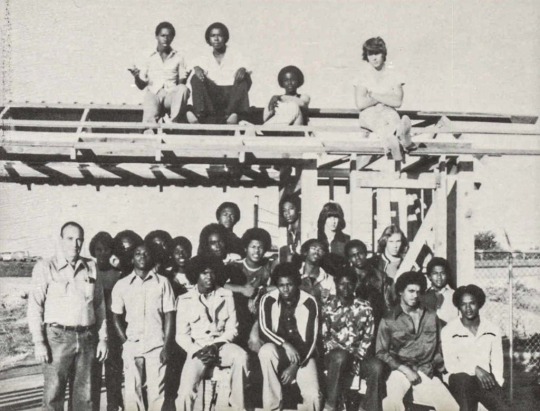

The VICA Building Trades club at Mexia High School in 1979, which included Carl Baker, Anthony Freeman, and Jay Wallace.Gibbs Memorial Library

Black Texans knew Mexia for something entirely different: it was the site of the nation’s greatest Juneteenth celebration. The holiday commemorates the day in 1865 when Union general Gordon Granger stood on the second-floor balcony of the Ashton Villa, in Galveston, and announced—two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation—that enslaved people in Texas were, in fact, free. Word spread throughout the state and eventually reached the cotton-rich region of Limestone County. Formerly enslaved people in the area left plantations and resettled in tiny communities along the Navasota River with names like Comanche Crossing, Rocky Crossing, Elm, Woodland, and Sandy.

They had to be careful. Limestone County, like other parts of Texas, was a hostile place for newly freed African Americans. In the decade after emancipation, the state and federal governments had to intervene in the area on multiple occasions to stop white residents from terrorizing Black communities. Historian Ray Walter has written that “literally hundreds of Negroes were murdered” in Limestone County during Reconstruction.

The region’s first emancipation festivities took place during the late 1860s, in and around churches and spilling out along the terrain near the Navasota River. “If Blacks were going to have big celebrations,” said Wortham Frank Briscoe, whose family goes back four generations in Limestone County, “they had to be in the bottomlands, hidden away from white people.”

Over time, several smaller community-based events coalesced into one, gravitating to a spot eight miles west of Mexia along the river near Comanche Crossing. There, families would spread quilts to sit and listen to preachers’ sermons and politicians’ speeches. Women donned long, elegant dresses, and men sported dark suits and bowler hats. They sang spirituals, listened to elders tell stories of life under slavery, and feasted on barbecued pork and beef.

In 1892 a group of 89 locals from seven different communities around Limestone County formed the Nineteenth of June Organization. Six years later, three of the founders and two other men pooled $180 and bought ten acres of land along the river. In 1906 another group of members purchased twenty more acres. They cleared the area, preserving several dozen oak trees, alongside which members bought small plots for $1.50 each. The grounds were given a name: Booker T. Washington Park.

The celebration continued to grow, especially after oil was discovered in Mexia, in 1920. Some of the bounty lay under Black-owned land, and money from the fields gave the Nineteenth of June Organization the means to build the park’s tabernacle and a pavilion with concession stands. During the Great Migration, as Black residents left Central Texas for jobs in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, they took Juneteenth with them, and word spread about the grand festivities along the Navasota River. Every year, more and more revelers came to Comanche Crossing, bringing their children and sometimes staying the entire week. Some built simple one-room huts to spend nights in; others pitched Army tents or just slept under the stars. During the busiest years, attendance reached 20,000.

James Ferrell’s Black Frontier Riding Club on a trail ride to the Juneteenth celebration at Comanche Crossing, year unknown.Courtesy of James Ferrell

On the actual holiday, it was tradition to read aloud the Emancipation Proclamation, along with the names of the park’s founders. Elders spoke about the holiday’s significance, and a dinner was held in honor of formerly enslaved people, some of whom were still alive. “You instilled this in your children,” said Dayton Smith, who was born in 1949 and began attending Juneteenth at Comanche Crossing shortly before his first birthday. “It had been done before you were born, by your parents and grandparents. Don’t forget the Emancipation Proclamation.Your parents didn’t come here every year just because. They came because of the Emancipation Proclamation at Juneteenth.”

Kids would grow up going to Comanche Crossing, then marry, move away, and return, taking their vacations in mid-June and bringing their own kids. “It was a lifelong thing,” said Mexia native Charles Nemons. “It was almost like a county fair. If you were driving and you saw someone walking, you’d go, ‘Going to the grounds? Hop in!’ ”

At the concession booths, vendors would sell fried fish, barbecue, beer, corn, popcorn, homemade ice cream, and Big Red, the soda from Waco that became a Juneteenth staple. Choirs came from all across the country to sing in the tabernacle. Sometimes preachers would perform baptisms in the lake, which was created in 1961, when the river was dammed.

The biggest crowds came when Juneteenth landed on a weekend. Renee Turner recalled attending a particularly busy Juneteenth with her husband in the mid-seventies. “My husband was in the service, and we couldn’t even get out,” she said. “He had to be back at Fort Hood that Monday morning, and so I remember people picking up cars—physically picking up cars—so that there would be a pathway out.” Everyone, it seemed, came to Juneteenth at Comanche Crossing. Daniel Keeling was an awestruck grade-schooler when he saw Dallas Cowboys stars Tony Dorsett and Drew Pearson walking the grounds. “If you were an African American in Dallas or Houston,” Keeling said, “you made your way to Mexia on the nineteenth of June.”

Even as Mexia’s Black residents took great pride in the annual Juneteenth festivities at the park, back in town they were still denied basic rights. Ferrell, who started spending the holiday at Comanche Crossing as a kid in the fifties, recalled life in segregated Mexia. “Up until the sixties, you still had your place,” he said. “If you were Black, you drank from the fountain over there, whites drank from the one over here, and if I went and drank in the fountain over here, well, I got a problem.” Back then, many Black residents lived near a commercial strip of Black-owned businesses called “the Beat,” along South Belknap Street, where they had their own movie theater, grocery stores, barbershops, juke joints, cleaners, and funeral home. When white and Black residents found themselves standing on opposite street corners downtown, the Black pedestrians had to wait for their white counterparts to cross first. “We couldn’t walk past each other,” said Ray Anderson, who was born in 1954 and went on to become Mexia’s mayor. “And if it was a female, you definitely better stay across the street or go the other way. You grew up knowing you couldn’t cross certain boundaries or you’d go to prison—or get hung.”

For years, the only law enforcement at Lake Mexia during Juneteenth consisted of a few well-known Black civilians. One was Homer Willis, an older man who had been deputized by the sheriff to walk around with a walkie-talkie, which he could use to radio deputies in case of an emergency. In the late seventies, more rigorous licensing requirements made such commissions a thing of the past, and the sheriff set up a command post across the lake where officers would hang out and wait. They stayed mostly on the periphery, helping to direct traffic and occasionally crossing the lake to break up a fight.

Until June 19, 1981, when, during the peak hours of one of the biggest Juneteenth celebrations in years, three officers piled into a small boat, started the motor, and cruised across narrow Lake Mexia.

The concession stands at Booker T. Washington Park.Photograph by Michael Starghill

When Baker and Freeman’s dual funeral was held in Mexia, so many mourners planned to attend the service that it had to be convened at the city’s largest church, First Baptist. Even so, the 1,400-seat space couldn’t accommodate them all. Baker and Freeman were remembered as kind young men who never hurt anyone and never got in trouble. At one point, Freeman’s mother, Nellie Mae, broke down, fainted, and had to be carried out. She insisted on returning for one last look at her only child before she was rushed to the hospital.

The district judge in Limestone County, P. K. Reiter, hoped that a swift investigation would defuse the escalating racial tensions. “We need to clear the air,” he said, announcing the opening of a court of inquiry, a rarely used fact-finding measure intended to speed up proceedings that would normally take months to complete. The court lacked the authority to mete out punishment, but it could refer cases for prosecution. Reiter asked the NAACP to recommend a Black lawyer to lead the inquest. The organization sent Larry Baraka, a 31-year-old prosecutor from Dallas. Baraka arrived in town two days after Booker’s body was found.

Limestone County had never seen anything like this. News helicopters flew into Groesbeck from Dallas and Fort Worth, landing in the church parking lot across the street from the courthouse. It was summer in Central Texas, and the courtroom, which lacked air conditioning, was crammed with 150 people; reporters filled every seat in the jury box. A writer from the Mexia Daily News wrote that the room was loaded with a “strong suspicion of intrigue, deep pathos, heavy remorse, and indignation.”

The main issue was the handcuffs. Eighteen witnesses testified, including Drummond, the probation officer. He insisted that the officers had brought just one pair of handcuffs, that only Baker and Booker were handcuffed to each other, and that the cuffs had been removed before they got into the boat. A witness who’d been on a nearby craft—a Black woman from Dallas—told the court that she saw the officers remove the restraints from two men who’d been handcuffed together. The fire chief testified that no cuffs were found on the bodies as they were pulled from the lake.

Other witnesses contradicted the officials’ version of events. Beachum, the hot-dog seller, again said that he saw cuffs taken off Baker’s body after it was retrieved from the lake, but he also admitted to drinking almost a fifth of whiskey that day. Another said all three were handcuffed—and that Elliott was drinking beer and his eyes were “puffy.” The local funeral home director, who had seen some two hundred drowning victims in his seventeen-year career, said that the position of Baker’s hands indicated that the teen had been cuffed. “It’s highly unlikely you will find a drowning victim’s hands in that position.”

At the end of the three-day proceeding, Baraka told reporters that the evidence suggested the teens were not handcuffed in the boat. He believed the officers had acted without criminal or racist intent, but he added that they had behaved with “rampant incompetence” and “gross negligence.” The boat was overloaded and there were no life preservers, so the officers could still face criminal charges.

For Mexia’s Black residents, the court of inquiry had cleared up nothing. They rejected the testimony of both Drummond and the fire chief and suspected a cover-up. Whites in Mexia also criticized the officers’ judgment. “You put a gun on someone’s hip, and it goes to their head,” former district attorney Don Caldwell told a reporter. “The evidence in this case doesn’t add up. It was a terrible act of stupidity, and somebody is going to have to pay the fiddler.”

That fall, Limestone County attorney Patrick Simmons, together with a lawyer from the state attorney general’s office named Gerald Carruth, took the court of inquiry’s findings to a grand jury. They hoped the panel would indict the officers for involuntary manslaughter, a felony. Instead, the jury came back with misdemeanor charges for criminally negligent homicide and violating the Texas Water Safety Act. If found guilty, the officers faced a maximum penalty of one year in prison and a fine of $2,000 per teen. “I could get that much for starving my dog,” said Kwesi Williams, a spokesperson for the Comanche Three Committee, an advocacy group formed in response to the drownings.

Defense attorneys argued that the officers couldn’t receive a fair trial in Mexia, so they requested the proceedings be moved. A judge in Marlin, about forty miles away, said he didn’t want it, not after “statements in the news media by certain persons created an atmosphere in this county that is charged with racial tension to the point that violence is invited.” The case was moved to San Marcos, where another judge punted. “No one wants this,” Joe Cannon, the attorney defending Drummond, told a reporter. “It’s a hot potato.” Finally, Baraka, who had by then joined the prosecution, convinced Dallas County Criminal Court judge Tom Price to preside over the trial.

If found guilty, the officers faced a maximum penalty of one year in prison and a fine of $2,000 per teen. “I could get that much for starving my dog,” said Kwesi Williams.

Price, who was eight years into a four-decade judicial career, would later call the Mexia drownings the biggest case he ever handled. “It was a hard, emotional trial,” he said. “Three young kids who died for no reason. There was so much tension, and it was so racially mixed up in there. I was thirty-three, thinking, ‘What have I got myself into?’ ”

The trial, which lasted three weeks, was perhaps the highest-profile misdemeanor proceeding in Texas history. Each defendant had his own attorney, and each attorney objected as often as possible, squabbling with prosecutors and spurring Price to threaten them all with contempt. The atmosphere was further strained by the presence of news crews, who swarmed the legal teams and the teens’ families during recesses.

To convict the officers of criminal negligence, the all-white, six-person jury would need to be convinced that under the same circumstances an ordinary person would have perceived a substantial risk of putting the teens into the boat and avoided doing so. Defense lawyers acknowledged that the officers had made mistakes but argued that their actions were reasonable—that they had needed to use the boat to avoid what they viewed as a hostile crowd. Two defense witnesses said they had seen the officers remove handcuffs from the teens before boarding the boat. Beachum, the witness who told the court of inquiry he’d seen handcuffs on Baker’s body, didn’t testify at trial because the prosecution didn’t call him to the stand. “I think Carruth, Baraka, and I all had problems with his credibility,” Simmons said recently. Instead, the prosecutors centered their case on other facts—from the absence of lights and life jackets aboard the boat to the officers’ reckless decision to overload the craft. “They made mistakes that would shock the consciences of reasonable people,” Baraka told the jurors.

The officers took the stand and said they had tried to save the teenagers. Archie told the jury that while he clung to the overturned boat, Drummond pushed Freeman toward Archie, who grabbed the thrashing teen by the hair and shirt and pulled him onto the hull. Archie said he tried to maneuver to the other side of the craft while holding Freeman across the top but the teen slipped off, sank, and then bobbed up four times before disappearing. Archie didn’t try to rescue him again because the reserve deputy wasn’t a strong swimmer. Drummond testified that he tried to help Baker but the teen kept pulling him under, so the officer let go and swam to shore. He also said that if he could have done anything to change the situation, he “wouldn’t have made an arrest in the first place.”

Elliott acknowledged that he and the other officers had erred. He called the drownings “just a horrible accident” and said he’d do things differently given another chance. When Baraka asked Elliott if he thought they deserved forgiveness, the deputy answered, “Under the circumstances, yes.”

After the closing arguments, the jury took less than five hours to render a verdict: not guilty. The defendants, showing no emotion, were rushed away. Afterward, Nellie Mae Freeman sat on a bench outside the courtroom reading the Bible. “No,” she told a reporter, “justice was not done.” Evelyn Baker, Carl’s mother, said she had expected the verdict. “This is very terrible, but that’s Mexia for you, and that’s Limestone County. The Lord will take care of them.”

The families found more disappointment when it came to their last remaining legal option: civil lawsuits, in which the deputies and the county could be held responsible for negligence under a much lower burden of proof. Each family sued for $4 million in damages, alleging that their sons’ civil rights had been violated. In December 1983, they settled for a total of $200,000, or $66,667 per teen.

A local official told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that the county’s lawyers felt “very lucky” about the outcome. “We were just sitting on pins and needles hoping it would get as low as possible but we never really thought [the settlement] would get this low,” said Howard Smith, a county judge familiar with the civil case. Attorneys for the county made a lowball offer, and the families and their lawyers accepted it. “I was tired,” Evelyn said recently. “I was hurt, and I never did get to really grieve. They just really ran us through it.”

The pavilion at the park on April 21, 2021.Photograph by Michael Starghill

For many Black Mexia residents, Comanche Crossing was never the same after the drownings. “It just changed my whole life,” said Steen-Medlock, the teens’ schoolmate. “I never went back to another Juneteenth there.” Many others felt similarly. Attendance in 1982, the year after the drownings, was about two thousand, the lowest in 35 years. It wasn’t just that celebrants were fearful of being harassed, arrested, or worse. Comanche Crossing was sacred ground, land that had been purchased by people who had survived slavery, to ensure that they, along with future generations, would have a place to commemorate emancipation. Now that land had been defiled.

Texas had made Juneteenth an official state holiday in 1980, and celebrations of Black freedom spread to other cities. In 1982 Houston’s Juneteenth parade attracted an estimated 50,000 onlookers. As crowds moved elsewhere, attendance at Comanche Crossing’s Juneteenth ceremonies continued to decline. Arson attacks in 1987 and 1989 caused severe damage to the tabernacle and pavilion, and the structures had to be rebuilt. Concession booths were tagged with racist graffiti.

Many of those who’d grown up with the teens left town. “It was all eye-opening to our generation,” said Nemons. “This was the first thing I saw as far as being a real racial injustice. A lot of young Black folks said ‘I’m done’ and moved.” Over the years, Juneteenth crowds at Comanche Crossing dwindled even more, while the brush along the lake grew thicker and the buildings fell into disrepair. During the past decade, official attendance has sometimes dropped to less than a hundred. When the Nineteenth of June Organization elected former county commissioner William “Pete” Kirven as its new president in 2015, some locals felt optimistic. “I had a lot of hope,” said Judy Chambers, a municipal judge for the city of Mexia and a past member of the organization’s board of directors. She thought the group—and Comanche Crossing—could use some new blood.

That hope didn’t last. Although the new leadership cleaned up the park’s grounds and installed new light poles and swing sets, it also posted a sign banning alcohol, instituted a 1 a.m. closing time, and increased the law enforcement presence during Juneteenth. The new rules did not go over well. “Juneteenth is not worth going out there,” said a Mexia resident who had attended the festivities since he was a boy. “It’s not any fun. So many police you can’t enjoy yourself. I went in 2018. I didn’t like it. I haven’t been back.”

Echols, a member of the organization’s board of directors, said that despite the “No Alcohol” sign, members of the public are allowed to drink as long as they use plastic cups. He agreed that law enforcement had gone overboard in 2018 and “was scaring people away” but added that after the group expressed these concerns to the sheriff, the presence was reduced.

Simmons, the prosecuting attorney at the 1982 trial, is now the district judge for Limestone and Freestone Counties. “This was the Juneteenth place, and it’s a shame we lost that,” he said. “At the time, I looked at it as an incident that needed to be prosecuted. I look back on it now and say, ‘What a tragedy. What a shame.’ The ridiculous idea of going over—three guys in a boat—could they rethink it? It was such a tragedy, not just the loss of three young men but the whole Juneteenth.”

In recent years, awareness of Juneteenth has exploded. Some of that is due to a woman from Fort Worth named Opal Lee. In 2016, when she was 89, she set out to walk from Texas to Washington, D.C., to publicize a campaign to designate Juneteenth as a federal holiday. Last year, Lee collected 1.5 million signatures on a petition in pursuit of that goal, and in Congress, Texas senator John Cornyn and U.S. representative Sheila Jackson Lee filed legislation to take Juneteenth nationwide. The bills didn’t pass, though they have been reintroduced this year.

Perhaps the biggest factor wasn’t a petition or a bill, though, but the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020. In the weeks after Floyd’s murder, the Juneteenth holiday became linked with the national protest movement in support of Black lives. On June 19, hundreds of thousands of protesters hit the streets of New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, D.C., and Houston. All across the country, marchers carried Juneteenth banners as well as signs emblazoned with Floyd’s face and the names of other Black people killed by law enforcement.

Back in Mexia, locals drew a straight line from 1981 to 2020. “When I saw that video,” said Chambers, “it took me back to that place and time where Black men were getting killed on the streets of Limestone County by law enforcement—and back then it was just swept under the rug.” Steen-Medlock said watching the video immediately reminded her of her three friends who died 39 years earlier. “Those three deputies thought, ‘We have a right to do whatever we want to do’—and that meant putting these boys in a small boat, at night, handcuffed, with no life jackets,” she said. “That’s how they dealt with Black people. If it had been white kids, they would have said, ‘Call your dad to come get you.’ But when you’re Black, you’re not treated like that. You’re guilty.”

“It was all eye-opening to our generation,” said Nemons. “This was the first thing I saw as far as being a real racial injustice. A lot of young Black folks said ‘I’m done’ and moved.”

This history helps explain why Chambers, Steen-Medlock, and almost every other current or former Black Mexia resident still believe the teens were handcuffed in the boat. Chambers said she has spoken with witnesses who told her they were scared to testify forty years ago. “I don’t know if you live in a small town in the South,” she said, “but a lot of powerful people in town control others with things like mortgages and loans.” Echols said, “Back in those days, there was a fear of the sheriff’s department. A lot of guys may have had some problems with the law, so they didn’t come forward.”

The foreperson of the grand jury, Ray Anderson, said that jurors discussed the handcuffs at length and subpoenaed Beachum to testify about their presence, but Beachum never showed up. At the time, that spoke volumes to Anderson. “I was never presented enough evidence of handcuffs,” he said. “If I could’ve proved murderous intent, I would have been the first to vote on it. I would have said, ‘We need to make an example—right here.’ ” Now, almost forty years later, Anderson doubts the grand jury got the whole story. “I still feel there was a lot of stuff that didn’t come out.”

Most white officials involved in the case maintain that there was no evidence the teens were handcuffed in the boat. Instead, they cite other factors that could have caused the three to drown. “I’ve taught swimming for years,” said Cannon, the attorney who represented Drummond. “If you’re fully clothed and it’s dark and you’re not oriented correctly, then you panic. You easily panic. I was surprised that any of them got back.”

Daniel Keeling was ten in 1981, and he grew up in Mexia hearing about the handcuffs as a statement of fact. The drownings left him so unsettled that he eventually pursued a career in law enforcement, where he hoped to improve the field from within. Keeling also hoped that he might uncover the truth behind his hometown’s most controversial case.

“Supposedly Drummond took the handcuffs off,” said Keeling, who spent over seven years as a deputy in Hunt County and six more as a deputy constable in Dallas and now works as a corporate security manager. “Well, usually when you’re making an arrest, you put handcuffs on a subject and don’t take them off until you get where you’re going. Did the pressure come down on him to change his story? The blue shield is real. And telling the truth could ruin your whole career.”

What really happened that night? Keeling’s search convinced him that the answer will never be known.

Around Mexia, locals don’t talk about the drownings much anymore. “This is still very raw for a lot of people,” said Steen-Medlock. “They want to forget it ever happened.” The city boasts several colorful murals depicting local heroes and historical figures, but there’s no memorial for Baker, Freeman, and Booker—not at the park, not anywhere in town. There is also no official record of the 1982 trial in either Dallas or Limestone County because the officers had their records expunged. Legally, it’s as if they were never even arrested.

These days, most Black Mexia residents celebrate Juneteenth at home with family and friends. Some hold block parties; others attend events in nearby towns. Many use that week for family reunions, with faraway aunts and uncles taking vacation time to come home to Mexia. But most don’t go to Comanche Crossing.

None of the officers involved in the drownings agreed to speak with Texas Monthly for this story. Archie, who retired from his job as a security guard, lives close enough to Lake Mexia that he can see it from his porch. Drummond retired from a career running a fencing company; he declined when reached for comment, adding, “I’ve done that. It’s been a long time and it’s still relatively fresh on my mind, believe it or not.”